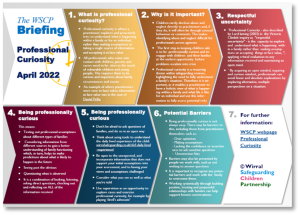

Professional Curiosity

What do we mean by ‘Professional Curiosity’?

Professional curiosity is a combination of looking, listening, asking direct questions, checking out and reflecting on information received and not accepting it at

face value. It means:

- testing out your professional assumptions about different types of families.

- triangulating information from different sources to gain a better understanding of family functioning which, in turn, helps to make predictions about what is likely to happen in the future.

- seeing past the obvious.

It is a combination of looking, listening, asking direct questions, checking out and reflecting on ALL the information you receive.

An example of a case where professionals took a lot of information at face value is the tragic case of Daniel Pelka.

Why is Professional Curiosity important?

It enables a practitioner to have a holistic view and understanding of what is happening within a family, what life is like for a child or young person and fully assess potential risks.

Professional curiosity means exploring every possible indicator of abuse and neglect and trying to understand what the life of the child is like on a day-to-day basis; their routines, thoughts, feelings and relationships with family members.

In order to be truly curious about a child’s life professionals also need to maintain an attitude of respectful uncertainty. This means applying a critical eye to the information given by a child’s parents/carers, rather than just ‘taking their word for it’.

A lack of professional curiosity can lead to missed opportunities to identify less obvious indicators of vulnerability or significant harm. We know that in the worst circumstances this has resulted in death or serious abuse as confirmed by the learning from case reviews, both nationally and locally where practitioners have responded to presenting issues in isolation. Lack of professional curiosity is a recurring theme in may local and national reviews.

How to be professionally curious

Don’t be afraid to ask questions of families, and do so in an open way, so they know that you are asking to keep the children safe, not to judge or criticise.

Be open to the unexpected, and incorporate information that does not support your initial assumptions into your assessment of what life is like for the child in the family.

Seek clarity either from the family or other professionals.

Be open to challenging, or having challenged, your own assumptions, views and interpretations as to what is happening – triangulate the information you hold.

Consider what you see as well as what you’re told. Are there any visual clues as to what life is like, or which don’t triangulate with the information you already hold?

Supervision and professional curiosity

Supervision is an opportunity to explore cases therefore, practitioners and supervisors should be open to exploring professional curiosity within supervision sessions:

- Play ‘devil’s advocate’

- Present alternative hypotheses

- Present cases from the child, young person, adult or another family member’s perspective.

Professional curiosity from afar

Due to the pandemic practitioners may have been working differently with children, young people and families, and in some instances this will include connecting with people via phone or video call. This has shown that there are alternative ways of working with families and such contacts may continue to become common practice where appropriate. However this does make engaging professional curiosity more challenging.

When making contact with a child or family member on the phone or by video call, the usual clues that help you detect any safeguarding issues, won’t be available to you, meaning that we need to think of more creative ways to identify how we implement professional curiosity.

Here are some tips to help you:

On the phone, ask:

| Can you speak freely?

Are there other members of the family in the room that can hear our conversation? |

By asking the child or family member if they can talk openly (closed question) should give you an indication of whether there is the potential for guarded answers to your question. By establishing this at the very beginning you can reduce the pressure on them. |

| Can you move to another room? | Asking them if they can talk in another room or outside might help them to talk more openly. It may be that you might need to talk another time. |

| Agreeing a code word | Agreeing a code word between you and the person you are talking to so you can quickly establish on further meetings whether that person can talk safely and openly. |

It should be recognised that children or families that cannot talk openly means there may be coercion and controlling behaviour within that family

Video calls

Consider the following:

- Is there anything about what you are seeing which prompts questions or makes you feel uneasy or concerned?

- What is the body language telling you?

- Are you observing behaviour which is indicative of abuse or neglect?

- Does what you are seeing support or contradict what you are being told?

Barriers to professional curiosity

A lack of professional curiosity can lead to missed opportunities to identify less obvious indicators of vulnerability or harm; assumptions made in assessments which are incorrect can lead to the wrong intervention for children and families. Being professionally curious is not always easy. There may be barriers to this, including those from practitioners themselves such as:

- Over optimism

- Making assumptions

- Lacking the confidence or assertiveness to ask sensitive questions

- Unconscious bias (as seen in the Child Q CSPR)

Barriers may also be presented by people we work with, such as not wishing to answer questions, questioning a practitioners’ intentions and what some organisations call disguised compliance.

It is important to recognise any potential barriers and work with the child, young person or family to overcome these. Working systemically through building positive, trusting and purposeful relationships with families can help support honest conversations.

7 Minute Briefing