Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

What are ACEs?

Childhood experiences have a massive impact on lifelong health and opportunity. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) refer to stressful or traumatic events that children and young people can be exposed to as they are growing up. ACEs range from experiences that directly harm a child, such as physical, verbal or sexual abuse, and physical or emotional neglect, to those that affect the environments in which children grow up, such as parental separation, domestic violence, mental illness, alcohol abuse, drug use or imprisonment. There is however a distinction between ‘normal’ stressful life events, such as parental divorce or illness of a loved one, and adverse childhood experiences, very traumatic life events, such as being or seeing someone else physically or sexually abused. These are experiences that will often be associated with post-traumatic stress disorder

What do we know about ACEs?

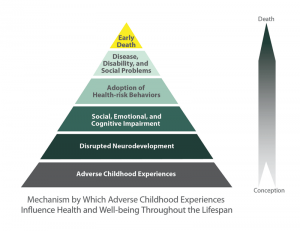

The original ACE Study was conducted in Southern California, at Kaiser Permanente from 1995 to 1997. Around 17,000 mostly white, middle class college-educated people completed surveys about their childhood experiences and current health status and behaviours, and received physical examinations (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2016). The findings of this research resulted in the development of the ‘ACE Pyramid’, which represents the link between childhood experiences, and adult health and wellbeing outcomes:

(Please click image for full page picture).

In 2012, the Centre for Public Health ran the first UK study in Blackburn with Darwin (BwD; Bellis et al, 2014a) using internationally validated ACE tools. This found that increasing ACEs were strongly associated with adverse behavioural, health and social outcomes across the life course. Subsequently, a national ACE study was undertaken in England in 2013. This found that almost half of the general population reported at least one ACE and over 8% reported four or more (Bellis et al, 2014bc).

The impact of ACEs

When exposed to stressful situations, the “fight, flight or freeze” response floods our brain with corticotrophin-releasing hormones (CRH), which usually forms part of a normal and protective response that subsides once the stressful situation passes. However, when repeatedly exposed to ACEs, CRH is continually produced by the brain, which results in the child remaining permanently in this heightened state of alert and unable to return to their natural relaxed and recovered state. Children and young people who are exposed to ACEs therefore have increased – and sustained – levels of stress. In this heightened neurological state a young person is unable to think rationally and it is physiologically impossible for them to learn or develop in the same way a child not having these experiences will.

ACEs can therefore have a negative impact on development in childhood and this can in turn give rise to harmful behaviours, social issues and health problems in adulthood. There is now a great deal of research demonstrating that ACEs can negatively affect lifelong mental and physical health by disrupting brain and organ development and by damaging the body’s system for defending against diseases. The more ACEs a child experiences the greater the chance of health and/or social problems in later life.

ACEs research shows that there is a strong dose-response relationship between ACEs and poor physical and mental health, chronic disease (such as type II diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; heart disease; cancer), increased levels of violence, and lower academic success both in childhood and adulthood.

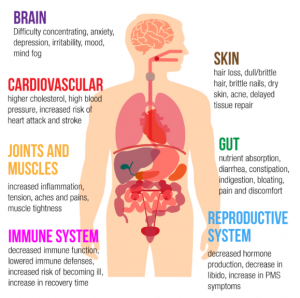

The effects of stress on the body

(Please click image for full page picture).

Outcomes and behaviours Adverse Childhood Experiences have been linked to:

|

|

The more ACEs in a childs life the higher the risk for these outcomes.

How can we respond to ACEs?

The ultimate aim for ACEs informed practice is to create a society in which ACEs occur far less frequently, and where they do the child and the family are offered support at the earliest opportunity. However this is not always achieved and often we will come into contact with the child/family after the ACEs have occurred.

In the case where a child discloses trauma there are things we can do to try and negate the impact of those experiences:

- Firstly we need to listen to the childs experiences. Think about how those experiences will have an impact on their healthy development and on their behaviours.

- Recognise the signs, and see beyond a child just ‘acting out’.

- Try to help them become more grounded, give them choices and allow them to feel more in control.

- Understand that it is likely this will have an impact on any attachment for that child and there will be mistrust. We need to try and build a relationship with the child that is different to ones they have experienced previously.

- Finally, it is important to remember that ACEs tend to be passed from generation to generation if parents do not receive support to reflect upon childhood stressors, and to explore how these may feed into current problematic behaviours and ongoing health issues, this in turn will impact on their ability to parent well.

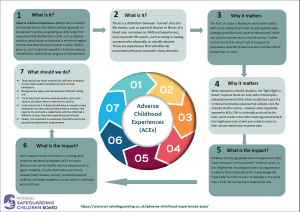

Seven Minute Briefing:

Further resources:

With thanks to Blackburn and Darwen Council.

Research in Practice have published the two briefings below which are designed to support staff and managers using trauma-informed practice (click on picture to access documents)

Beacon House in Sussex and Chichester is a clinic offering a wide range of mental health assessments and effective therapies for children and young people, families and adults who are experiencing mental health difficulties, emotional and behavioural problems and relationship conflict. As a service they have a specialist interest in repairing the effects of trauma and attachment disruption and through their website provide some really useful resources for both professionals and families (click on picture to access website).